For centuries, castles have been portrayed in art. Whether through realist depictions, attempting to accurately record what the artist of the day saw, or a romantic or picturesque interpretation, artists have influenced our perceptions of these fortifications. Most recently, photography and digital reconstructions have expanded the options available to artists – although conventional media continue to be popular. This article provides a brief introduction to the history of English and Welsh castles in the arts, from the 11th century to the 21st.

History

11th-16th centuries

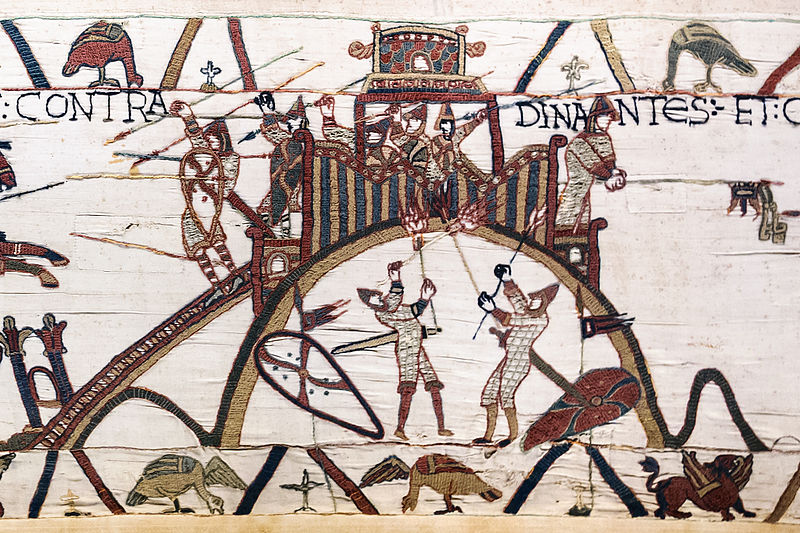

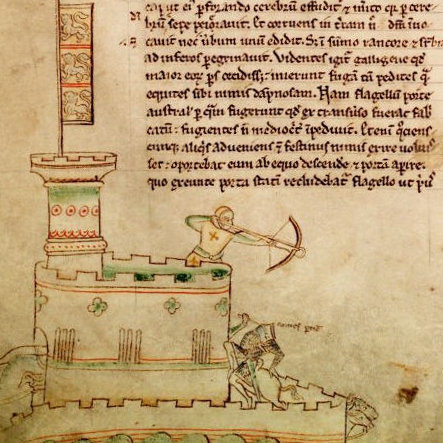

There are few surviving pictures of our early castles. The 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry shows the construction of the motte-and-bailey castle at Hastings, for example, alongside various castles in Normandy, but this depiction was probably unusual even at the time.

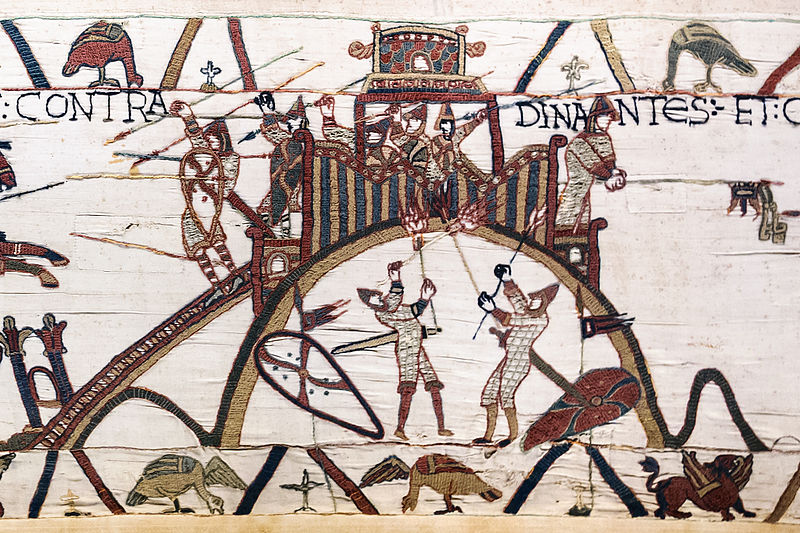

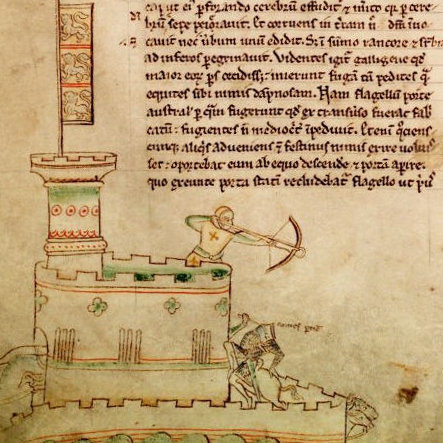

In the middle of the 13th century, the Benedictine monk and chronicler Matthew Paris recorded various views of contemporary life in the margins of his works. In the Chronica Majora he sketched Lincoln Castle during the First Barons’ War, creating a rare glimpse of a turreted fortification, complete with crossbowman and the royal banner flying over the top of the castle. Bedford Castle is depicted in a similar style during its capture by royal forces in 1224. Montgomery and Gannock castles receive slightly different treatment, being represented as multi-towered defences, the latter with the waves of the Conwy estuary added below.

As the historian Suzanne Lewis notes, Paris’s drawings – often inventive and fluid – should be seen as “pictorial commentary”, rather than than straightforward illustrations, but they do give a glimpse of the English and Welsh castle as perceived by a contemporary observer.

Later illustrated manuscripts also featured some images of castles. The 14th-century French chronicler Jean Froissart depicted various English and Welsh castles, but few with any accurate detail. Soon after, Jean Creton, another French chronicler, depicted Flint Castle – but, like Froissart’s work, the details were largely imaginary. Such works do, however, give us a sense of the important features of castles to contemporaries – tall towers, conical roofs, long crenelated walls, huge gatehouses.

A late-15th century manuscript, in contrast, depicted the imprisonment of Charles, the Duke of Orleans, providing a realistic and detailed depiction of the Tower of London, including the White Tower and the Traitors’ Gate facing on the River Thames.

17th-18th centuries

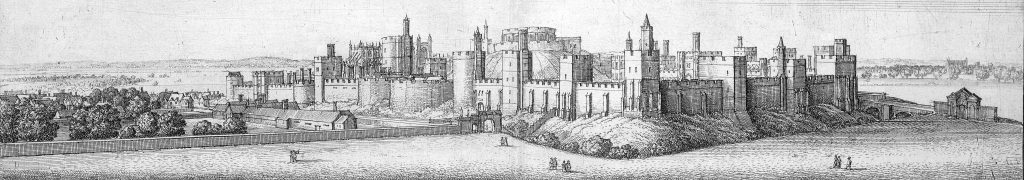

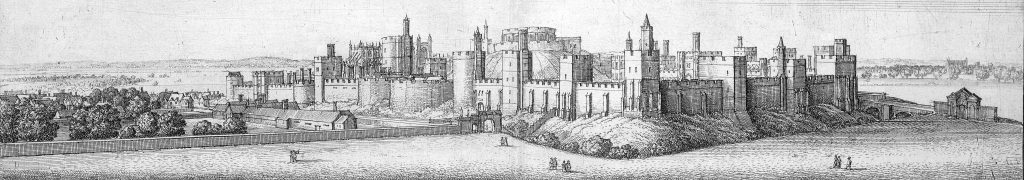

Although many castles were slighted after the English Civil War, in some cases we have accurate records of their appearance, due to the work of the Bohemian artist Wenceslaus Hollar. Hollar came to England from Prague in 1636, and produced various mid-17th century etchings and watercolours of English castles, including Windsor and Arundel. Hollar’s style was typically accurate, with close attention to detail, often using of bird’s eye views – a trend that would prove popular throughout the rest of the century.

Architectural studies in the first half of the 18th century were dominated by the Bucks Brothers. Samuel Buck, supported by his brother Nathaniel, copied the commercial approach pioneered by Leonard Knyff and Johannes Kip in the early years of the century. They would take on wealthy clients with large medieval properties, record the houses or castles during the summer, turn these into engravings in the winter, and then publish the pictures the following year. They produced 81 views of towns, and 423 of medieval sites, not all of them entirely accurate in their depictions. Their detailed works were collected and published in 1774, and widely reprinted in later years.

During the second half of the century, Paul Sandby produced a range of accurate watercolours of castles and other landscapes. By the mid-18th century, “history painting”, which covered both secular and religious narrative history, was greatly prized, and often included real fortifications in its depictions.

By the 1770s, however, the Picturesque movement became increasingly well established. The movement championed the sublime aesthetic, encouraging the visualisation of castles as ruins, part of a dramatic landscape. The Wye Valley tour along the Welsh borders popularised such art, much of which took considerable licence with the original features.

19th century

J. M. W. Turner painted many British castles around the turn of the century, often in watercolours. Many of these works took a sublime perspective towards the sites, often taking considerable artistic licence with the terrain, or exaggerating the scale of the buildings. He also undertook a very large number of drawings in preparations for his painted works, and many of these have also survived. Turner was willing to include more modern features in his work, and early 19th century technology and commercial aspects appear in many of them.

In 1814, Sir Walter Scott published his novel Waverley. Immensely popular, it encouraged a wider Romantic movement that reimagined Britain’s past as an alternative to the rapidly industrialising present. Ivanhoe, published in 1820, featured a tournament held at Ashby-de-la-Zouch castle. Castles featured prominently throughout in Romantic art, part of what historian Tim Craven characterises as an attempt to embrace the heroic past.

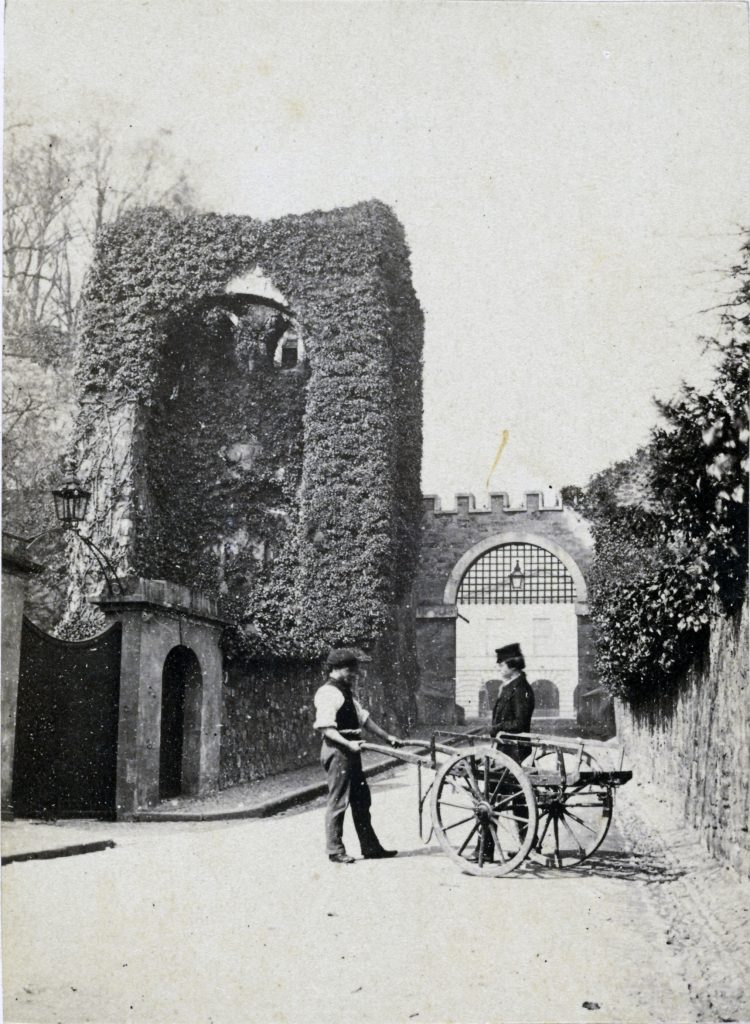

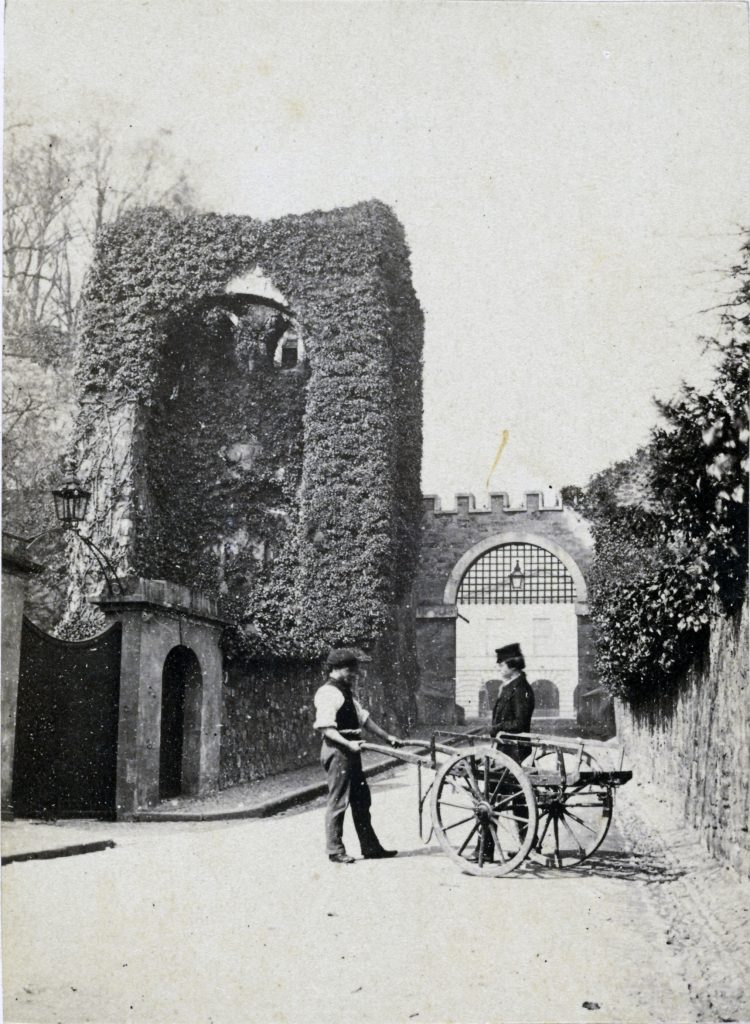

During the early Victorian period, interest in castles as ivy-clad ruins persisted. Artists such as Edward Blore, John C Buckler, and R. W. Billings – who often also worked as architects – recorded many British castles and other medieval buildings through detailed sketches and aquatints.

Meanwhile, castles first began to be photographed in the 1840s using salted paper, and Frederick Scott Archer began to use the wet collodion process in the 1850s, enabling him to produce much sharper commercial photographs of castles and other ancient buildings. This tradition was continued by the amateur photographer, Benjamin Brecknell Turner, and became a mainstream technique after 26 photographs were used to illustrate the 1862 volume Ruined Abbeys and Castles of Great Britain and Ireland. Photographs became increasingly used in guidebooks, and in 1896 they were extensively used within J. D. Mackenzie’s popular history, Castles of England: Their Story and Structure.

Francis Frith, and J. Valentine and his sons, competed for the early postcard market in the 1850s and 1860s, recording hundreds of images of castles. Stereoscopic images, which gave the illusion of depth, enjoyed popularity after their display at the 1851 Great Exhibition. Castles also began to be depicted through the medium of ground plans, taking advantage of the architectural and engineering skills increasingly used in Victorian projects.

By the end of the 19th century, there was various attempts by artists and historians to accurately reconstruct the historical appearance of British castles using archaeological and historical data. This was encouraged by the availability of cheap lithography in the national press, which led to a demand for these images, as well as the growing number of museums and art galleries. Many early films used castle ruins as sets, adding to their popularity.

20th-21st centuries

As the early 20th century progressed, an increasing number of castles found their way into the National Collection, managed by the government’s Office of Works. Many of these were photographed by the authorities as part of the restoration work that usually accompanied the sites being taken into care. There were relatively few illustrations made of how the sites might have looked in the medieval period, however, as the Office of Works had a policy that it “did not encourage or permit the exhibition of artists’ reconstruction drawing of monuments”, on the basis that it did not wish to be seen to favour one theory of the past over another.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, the government sponsored the “Recording Britain” project between 1940 and 1943. This employed artists to paint or sketch sites around the country, including many castles, and aimed to produce records of those buildings crucial to national identity that might be damaged by the war. These art works depicted the sites in their contemporary form, however , rather than using any form of reconstruction.

This policy shifted in the 1950s, driven by Lord Molson, the new Minister of Works, who commissioned a range of new illustrations.

The post-war depiction of castles was initially dominated by Alan Sorrell. His career had begun in the 1930s but was disrupted by the Second World War. Sorrell’s distinctive watercolours, based on detailed collaboration with historical experts, redefined the field and became widely used.

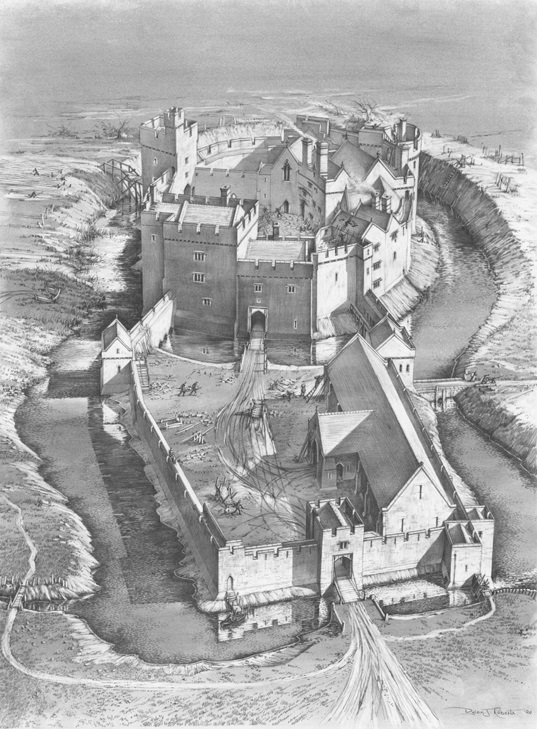

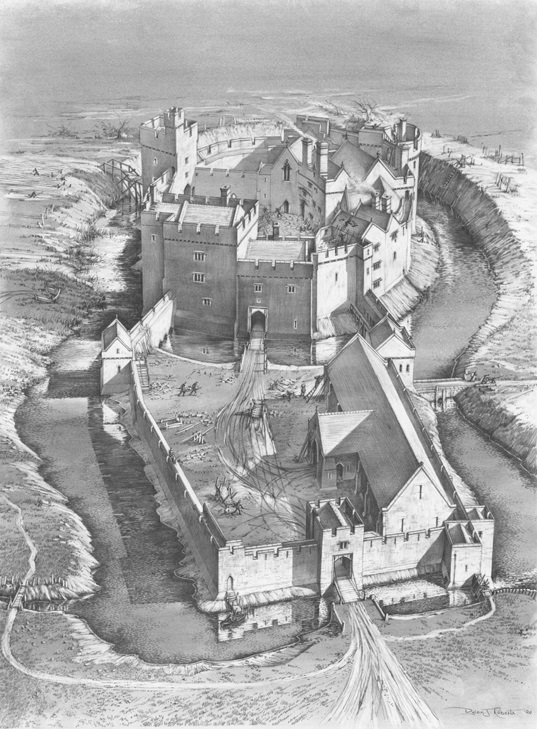

Sorrell paved the way for a clutch of other artists. Terry Ball and Ivan Lapper, were active from the 1980s onwards using watercolours, acrylics and ink and pencil. Dylan Roberts, black-and-white pen and ink works. Chris Jones-Jenkins followed suit in the 1990s, working in watercolour and inks. Their works have provided detailed, high-quality interpretations for several generations of guide books and visitor centres.

During the 1980s, computer-generated 3D models of castles began to be created using early graphics software. By the 2000s, these were increasingly sophisticated and, by the following decade, more reconstructions of the fortifications were being created. New software packages, backed by cheaper processing computer power, provided accessible options for new online artists.

British castles continued to be widely used as sets by cinema and television. The art historian Sam Smiles estimates that there have been over 140 such productions in the last 80 years.

Relatively few art exhibitions, however, have focused specifically on the theme of our castles. The Southampton City Art Museum held a major exhibition in 2017, entitled “Capture the Castle: British Artists and the Castle from Turner to Le Brun”, presenting both contemporary and historical works. A book accompanying the exhibition was published by Sansom. The same year, the Yale Centre for British Art held a exhibit on British Castles, subtitled “A Study in Stone”. The exhibition considered the artistic record of castles, from the perspective of them as both as inhabited spaces and symbolic constructs. The accompanying exhibition booklet is available online.

Bibliography

- Bryant, Julius. (1996) Turner: Painting the Nation. London, UK: English Heritage.

- Guy, Neil. (2016) Castle Studies and the Early Use of the Camera 1840-1914. Castle Studies Group.

- Lewis, Suzanne. (1987) The Art of Matthew Paris in the Chronica Majora. Berkeley and Los Angeles, US: University of California Press.

- Redknap, Mark. (2002) Re-Creations: Visualizing Our Past. Cardiff, UK: National Museums and Galleries of Wales, and Cadw.

- Sorrell, Alan. (1980) Early Wales Recreated. Cardiff, UK: National Museum of Wales.

- Southall, Stuart, Tim Craven, Sam Smiles, Roy Porter, Andy King, Anne Anderson and Steve Marshall. (2017) Capture the Castle: British Artists and the Castle from Turner to Le Brun. Bristol, UK: Sansom and Company.

Atttribution

The text of this page is licensed under under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Images on this page included those from the Wikimedia, Coflein, British Library and Getty websites, as of 23 November 2019, , and attributed and licensed as follows: “Bayeux Tapestry motte” (Public Domain); “Lincoln Castle” (Public Domain); “Windsor Castle” (Public Domain); “The North-east View of Scaleby Castle” (Public Domain); “Conway Castle” (Public Domain); “Rougemont Castle” (Public Domain); “Coity Castle“, author Coflein (Crown Copyright, Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales), released under Non-Commercial Government Licence v.1.0.